In my 30s, when I was less forward than I am now, I needed my mother to go ahead of me in the receiving line, wedding or funeral, to tell me which relative was coming up. To some extent, I can guess nowadays which child or grandchild belongs to whom. But mostly I just shove out my hand and say, “I’m Sharon’s daughter” or “My father was Harvey.” One or the other usually makes everything clear.

At Aunt Hannah’s funeral yesterday, I knew the aunts and the cousins by their faces. Nobody has changed much, except everyone is suddenly skinny. It’s the stress. It’s like a tapeworm as you age, eating you from the inside. My cousin Phyllis, the daughter of the newly departed, was always a favorite on my dad’s side. She sold me my first SLR, a Pentax Spotmatic, for $50, and I still have it and use it when I want to shoot film. In the ‘80s, when my now-husband was my secret boyfriend, I went to her wedding and later wrote a song about it for my new wave band, Question 47. “Bridal Gown” was one of our best songs.

My father was adopted by the father of three sisters—Hannah, Sydney, and Bluma. Bluma wasn’t at the funeral. She isn’t leaving the house these days except to drive, on her expired license, to the store. She was always good to me, with an infectious laugh and a wry sense of humor, despite having to grow up with Brick as her father. He was not kind to her. My grandmother, Sylvia, was my dad’s birth mom. His real dad remarried and didn’t want his eight-year-old son in his new family; his new wife wanted nothing to do with his past.

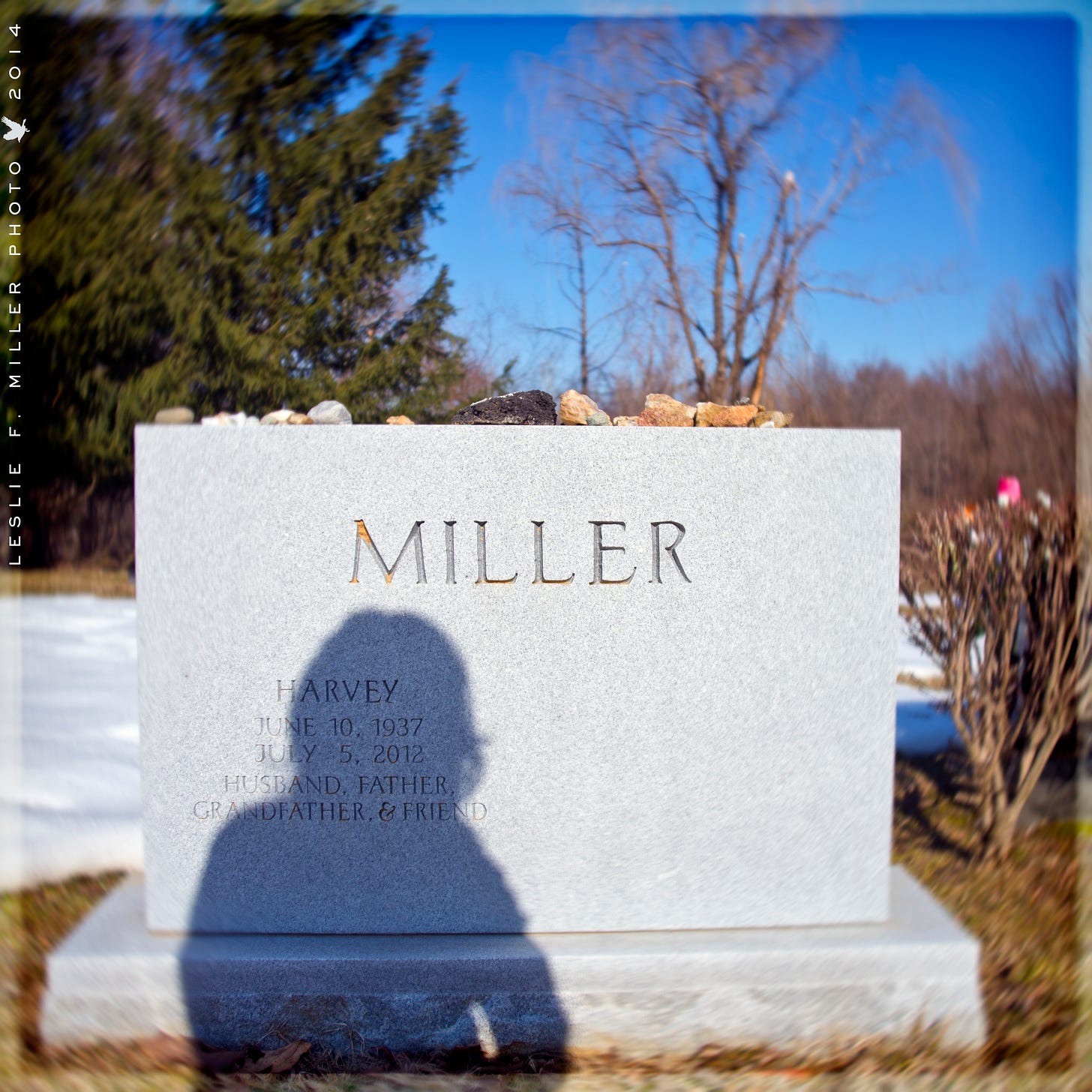

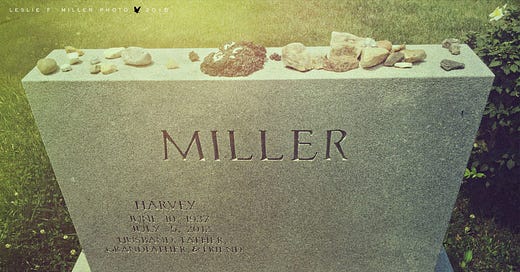

Sylvia was glamorous and smoked. What else would you expect from a Sylvia? Also, she died of lung and brain cancer, taking in smoke as her last breath, like you’d expect from a Sylvia. From what I remember, she wasn’t the best mother or the most loving grandmother. What I liked best about her was Vivian, her housekeeper. I went to Vivian’s funeral because I wanted to, not because I had to. I remember Gram Sylvia calling my dad from the nursing home, yelling, “HARVEY. I NEED MY CIGARETTES, HARVEY” on the answering machine, her smoky rasp almost a parody of itself. Dad ducked her as often as he could, but it pained him to feel that way. He was a good man. He gave Sylvia her cigarettes and his attention.

At his sister Hannah’s funeral yesterday, the teary grandchildren, 30-somethings I’d never met before, told stories I could relate to. I heard Hannah’s voice in them. Phyllis spoke, too, talking not only about their friendship but their difficult past two years, which is important and shouldn’t be taboo. People who die don’t automatically become saints.

My dad’s side of the family was warm and welcoming. I remember looking forward to our visits to Aunt Sydney’s, despite my being my unfriendly self. I remember her living room, her tchotchkes, the picture window. I remember cookouts and dinners and her warm and lovely husband, Harry, who died recently. I remember being shy around Philip, who died last year after a blood clot after surgery to correct a neck disc. I cried at his funeral, mostly because I wished I’d known him better.

I met my sister early to go through the receiving line, which we missed at Phil’s. My mom showed up shortly after, but I was already thrusting out my hand and announcing myself. I thought my cousin Sheryl’s son was her ex-husband, though, and said, “Greg?” Last time I saw him, that’s what he looked like. “That’s my son,” she said, with raised eyebrows, probably at my good memory.

Most funerals are sad. Even if you hated the son of a bitch in the box, you hurt for those who loved him. What broke our hearts more than the death of a 95-year-old relative was hearing Hannah’s life story from the rabbi. You would never know my father had been her brother since age eight.

My sister, Beth, was weeping in the parking lot afterward, which made me tear up. “He never belonged anywhere, even in death,” she said in crying gasps. Mom was upset, too—an honorary pallbearer, yet with no mention of my dead father and no adjective attached to her name in the obit; everyone else (ironically, even my dad) was a “loving,” “dear,” or “beloved” person.

I didn’t take it personally, though. You don’t have your wits about you when you’re grieving. And when you’re 95, your closest family members are up there in age, too. Can’t fault them. Can’t fault the cousin with the terminally ill daughter. Can’t fault women who’ve lost their moms. It’s like forgetting to name your agent or your husband when you win an Oscar or a Grammy. It’s an emotional moment.

I think we were just briefly untethered.

I used to say that I wanted a huge funeral, standing room only, filled with enemies and friends alike. I even wrote my own obituary: Here Lies Leslie. She Was Good on Facebook. My sister pointed out that I’d have to die young; otherwise, all those people would outlive me. She’s right. Maybe I want a funeral the size of my aunt Hannah’s. When you’re 95, you’re likely to be the last person in your friend group standing, which doesn’t sound like a fun option, either.

Just so beautiful and poignant.

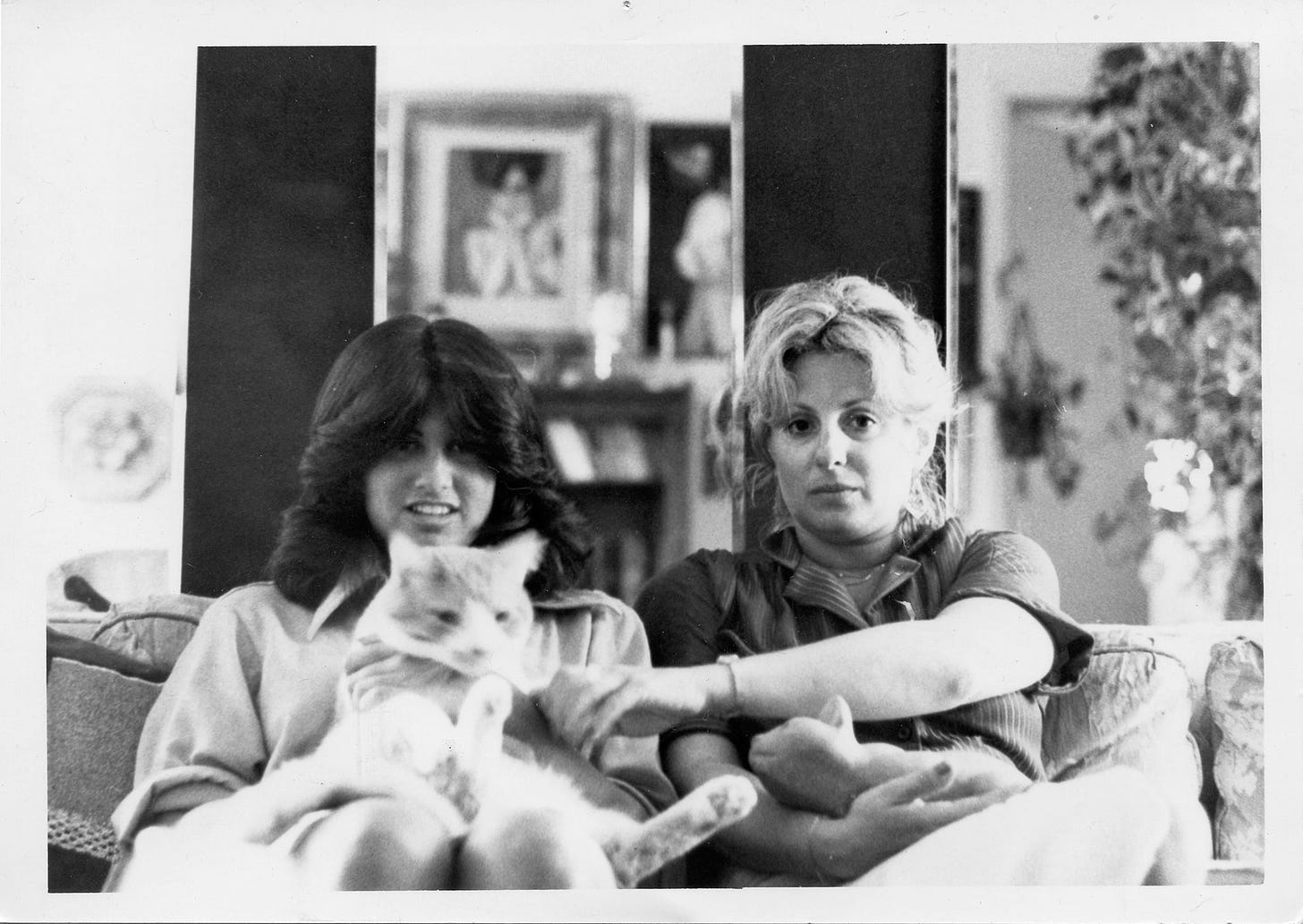

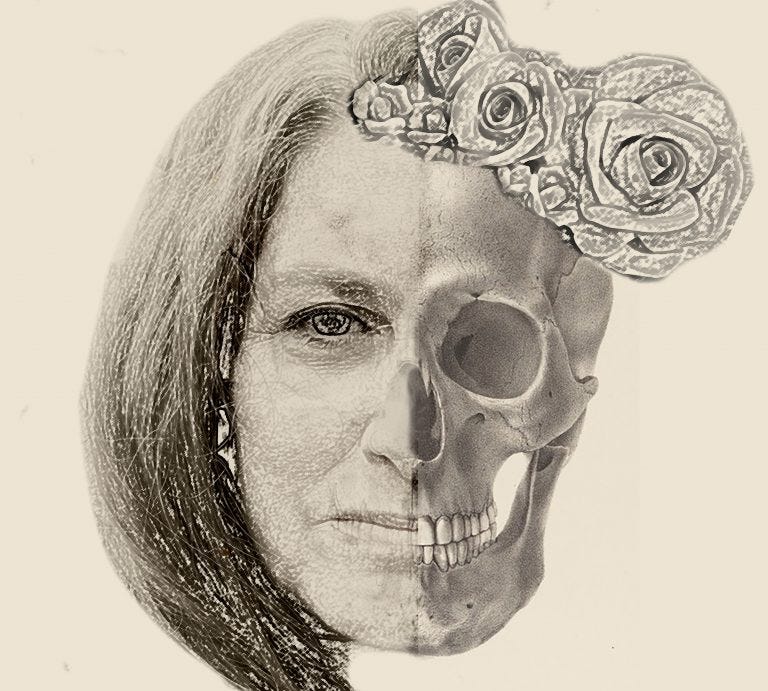

Heartbreaking but beautifully written. More hugs. Someone should write a book about people’s funeral experiences. (Siri suggested arrangements lol.) And I love that photo of you and your mom as well as the art.